SB Repertor · Traditional Thames Sailing Barge · Races, Day Trips, Weekends and Cruises

Enquiries and bookings, please call 07831 200018 or email us

Links

Sailing Barge Association

Organises the Sailing Barge Championship

Thames barge match

The official website of the match committee

Pin Mill barge match

The website

of the Pin Mill Sailing Club

Thames sailing barges

Very complete enthusiast’s site

Society for Sailing Barge Research

Preserving the history of sailing barges

The history of SB Repertor

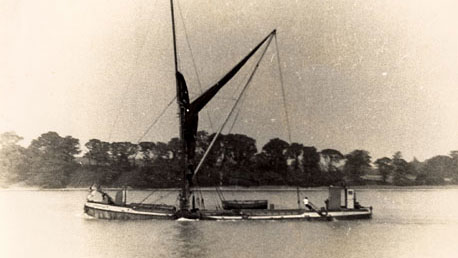

Repertor deep-laden alongside Customs House Quay in Ipswich Dock — still with full sailing rig

<< first | < previous | 1 of 6 | next > | last >>

The Horlock family owned many barges, trading along the Suffolk and Essex coast, across to North Kent and up the Thames to London.

Their barges would pick up cargoes from farms and rural wharves, from creeks and backwaters, from local ports and harbours, and sail through the channels and swatchways of the Thames Estuary and up the London River to the docks. They would carry grain, hay (for London’s horses), timber, bricks, stone, sand and gravel one way — returning with rubbish (for the brickworks), cement, animal feeds, fertiliser and manure (for the farms), paraffin, coal and acid (for heating and processing). It was a constant cycle of general trade.

The advantages of steel construction

The Horlocks were businessmen as well as sailors and, as ever in trade, were always looking for ways to gain commercial advantage. By the 1920s, some steel-hulled barges had already been in use for many years, but the great majority of barges were still timber-built. Steel barges offered the chance to load more cargo into a hull of the same overall size (because steel scantlings take up less volume than timber, for the same strength). They were also lighter in weight, giving increased speed of response, and had a longer life.

In 1924, Horlocks decided to build a new fleet of seven steel barges, of which Repertor was the first to be launched. Repertor could load up to 140 tons of cargo, considerably more than timber barges of the same overall size.

The move to motorisation

When she was built, Repertor was a pure sailing barge, only in the 1930s having auxiliary engines installed. Over the years, as more and more ships and barges became engine-powered, those powered by sail alone could not compete. Not only could a motorised barge make a speedier passage, she could also keep more reliably to delivery dates, being less subject to the vagaries of wind and tide.

So, gradually and in common with most other barges, Repertor had her sailing rig reduced and her reliance on engine power increased. First to go was probably her bowsprit (and her jib and jib-topsail with it); then her mizzen, with a deckhouse being added; then her topmast and topsail; and eventually her mainmast, mainsail and foresail.

Finally, she was converted into a tanker barge, with her mastdeck removed, her fore and main hatches combined and her hold filled with steel tanks, carrying acid for the trade between the River Lea (in London) and the Brantham works, near Mistley, which manufactured Xylonite, an early form of plastic that could burn underwater and was therefore used for fuses in torpedoes.

Retirement and restoration

Repertor was sold out of trade in the mid-1970s, with her engines stripped out, and became, for a time, a houseboat. Later in the same decade, however, she was converted back to being a sailing barge. On deck, she now once again looked — indeed was — very much as she had been in her trading days under sail. But below decks she was converted for private social and charter sailing; and in the late 1980s she was reconverted more specifically for comfortable charter cruising and racing.

Repertor today

What had been her cargo hold now contains living, cooking and sleeping accommodation, for up to 12 passengers and five crew. A surprising feature for many passengers, perhaps used to comparatively cramped yacht accommodation, is the great feeling of space below decks and the ability to walk upright without stooping (except for the very tall) from one end of the accommodation to the other.

So, now Repertor carries cargoes once again, but of people rather than of goods; and it is interesting, although logical, that her sailing areas remain broadly the same as when she was in trade. Thanks to her extremely practical design, Repertor can still sail in the most interesting waters of the East Coast — into creeks and backwaters, across shallows between swatchways and generally a long way off the beaten track.